“They are silent photographs that speak, insentient objects with desires, lifeless things with a social life, the embodied presence of absence.”

Some academics believe that the word archive is synonymous with document, that written documents are the sole primary source of historical narrative. In Indonesia, even though “archive” is defined as “all kinds of the records of events”1, many still heavily rely on the conventional archives when they conduct historical research, possibly because of the mainstream perception of archives, or perhaps because of the lack of knowledge on how to use the other types of archives. Therefore, when I saw the title of the book Michelle Caswell written, I knew that I would learn something new about visual records.

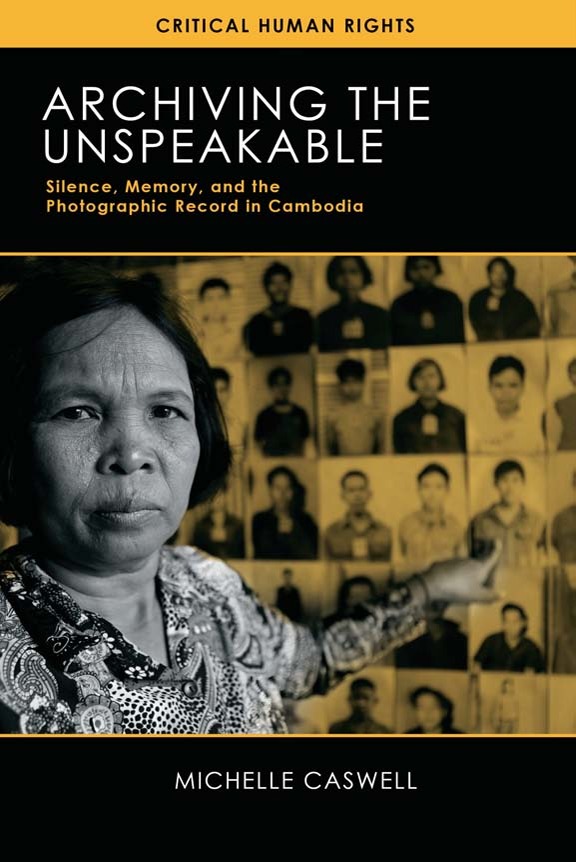

Archiving the Unspeakable. Silence, Memory, and The Photographic Record in Cambodia sheds a light on how important—and, at the same time, vulnerable—visual record is in the production of history. By employing the mug shots from Tuol Sleng prison in Cambodia, Caswell argues that photograph, as a type of records, has a powerful ability to unveil moments of silence and acts of silencing through its social life and actively influences people’s lives, society, and politics as an agent despite its silences.2 However, in the Tuol Sleng mug shots which are contained with violence, Caswell notes that the transformative power of creation and the complete oppressiveness of Tuol Sleng made the photographs “frustratingly silent”, thus projecting our voices to it can potentially address “a false sense of agency to deem the Tuol Sleng victims co-creator of the records used to murder them”.3 Moreover, there is also a debate about ethic of looking on the photographs depicting violence as Caswell asks, “How can we ensure that looking at these images is a political act of witnessing and not an exploitative act of voyeurism?”4 I think, these are the reason why researchers need to treat this kind of visual records carefully and critically.

Proposing a new way to understand, unveil, and produce historical narratives by employing visual records, Archiving the Unspeakable is a critical book to learn about the politics of archive and archiving. It is an essential contribution to postcolonial archival studies as Caswell proposes the use of record continuum model, which is a rather new approach in the studies.5 While acknowledging Trouillot’s framework of four moments of silences, Caswell also contests Trouillot linear model of history producing and prefer the continuum model which suits the need of digital age better by offering multidimensional, extend across space and time, and multilayered contexts. She also employes Appadurai’s theory of the social life of things to explain how photographs are not merely records, but also the active agents that speak and explain themselves.6 Consequently, with these approaches, Archiving the Unspeakable disproves the old approach that uphold written archives as the more trusted primary source of historical narratives and the linear model of the production of history.

Notwithstanding her refusal to Trouillot’s linear framework, Caswell acknowledges four moments when power is present in the producing of history by actively using them to structure her explanation in the book. To explain how the Tuol Sleng victims were silenced, and to answer why the Khmer Rouge regime necessitated to document their brutality, Caswell describes the creation of Tuol Sleng prison documentations employing Hannah Arendt’s theory of the banality of evil in the first chapter of the book.7 In the next chapter, while explaining the silences in the mug shots’ archiving process, she tries to response to the question why the mug shots and other documentations of Khmer Rogue brutality need to be preserved. The third chapter explores how the survivors, the family members of Tuol Sleng victims, and archivists using the Tuol Sleng mug shots to produce historical narratives, which in turn become the new records, contributing to an ever-evolving multilayered archive. The explanation employs the approach of record continuum model. Lastly, in chapter four, Caswell discusses her concern on the ethical side of the Tuol Sleng documentations and the memory of the victims using for commercial purposes as there is a potential commodification of the memory as well as the social function of the mug shots in a new form of archiving led by the new tourist-generated photographs.8 I find her way of organizing the book is very pleasant and comfortable to comprehend because of this outline. Not only does Caswell use a good framework to outline the book, but she also uses satisfactory sources and presents them in both end notes and bibliography lists. She cites and employs multiple approaches to explain and support her arguments, which are very effective.

Last of all, what intrigued me is the debate of ethics in the use of visual records, especially when they contain and depict violence. To whom the copyright of the images re-created from the Tuol Sleng mug shots should be addressed? To what extent we could use, or re-create, atrocious photography? In her article, Odumosu also stages the same questions, concerning the use and digitization of ethnographic images of Black people and slaves. She believes that such photographs are only continuing the slavery practice by transferring the enslaved body of manual labor “to the domain of visual, producing a surplus of images in different materials” for the Europeans.9 As she notes that describing the sanctity for atrocious images is not a simple task, Odumosu seeks a way to develop an ethics of care for digitization to raise awareness about where and how sensitivity is required before people re-create and re-using the photographs.10 Related to this, despite her warning about the potential decontextualization of the photographs as happened in the MoMA exhibition, Caswell suggests that people “have an ethical imperative to look at these photographs, as long as such looking is properly contextualized”.11

- The Indonesian Archival Law (Undang-Undang Nomor 43 Tahun 2009 tentang Kearsipan) ↩︎

- Michelle Caswell, Archiving the Unspeakable. Silence, Memory, and the Photographic Record in Cambodia (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 2015), p. 157-159 ↩︎

- Ibid., p. 158 ↩︎

- Ibid., p. 162 ↩︎

- Ibid., p. 13 ↩︎

- Ibid., p. 15 ↩︎

- Ibid., p. 52 ↩︎

- Ibid., p. 23-24 ↩︎

- Temi Odumosu, “The Crying Child: On Colonial Archives, Digitization, and Ethics of Care in the Cultural Commons”, Current Anthropology, volume 61, supplement 22, October 2020, p.s297 ↩︎

- Ibid., p.s298 ↩︎

- Caswell, op.cit., p. 164 ↩︎